“Barry’s dead, does no-one hear? Kilmichael’s road — what worth? While Irishmen wear rusty chains that beset them by their birth…”

Today, the 28th day of November 2020, marks one hundred years since a 21 year old Tom Barry lead the flying column of the 3rd West Cork Brigade, Irish Republican Army, into one of the most renowned battles against the forces of British occupation. Unbeknownst to those involved, fate would dictate that their coming fight would prove to be a turning point in the Tan War and one of the most remarkable enagements in the centuries old fight against British imperialism in Ireland. The Russians have Stalingrad, the French have the Bastille – and we have Kilmichael.

The Kilmichael Ambush was organised and planned in meticulous secrecy by Tom Barry and the leaders of the West Cork IRA, who drilled and trained the column for a solid week prior to their long march to the planned ambush site. Shortly after 3am on the morning of the ambush, and through pelting rain the column lead a solemn five hour march from Balineen to Kilmichael before falling into their carefully chosen positions. Here they lay in wait for eight more hours, in the cold and rain and almost an entire day since their last meal, in anticipation of the coming fight against the enemy – the Royal Irish Constabulary Auxiliary Division based in Macroom. Shortly after 4pm the enemy came into sight, loaded in two Crossley Tender lorries. Barry, dressed in a IRA officer’s uniform and armed with an automatic pistol and two Mills bombs, had taken up position in the centre of the road. As the first enemy vehicle slowed it’s approach, Barry threw one of the Mills bombs into the cab of the lorry, blew his whistle to signal open fire and began firing his own weapon.

The ensuing battle was bloody and quick, with many volunteers enagaging in hand to hand combat with the enemy. A brief cessation to hostilities came when some of the Auxies threw down their weapons and feigned surrender. As a number of IRA men lowerered their weapons the enemy again opened fire on the unsuspecting volunteers, after which Barry gave the order to not cease fire until he commanded so, or, until the enemy were all dead.

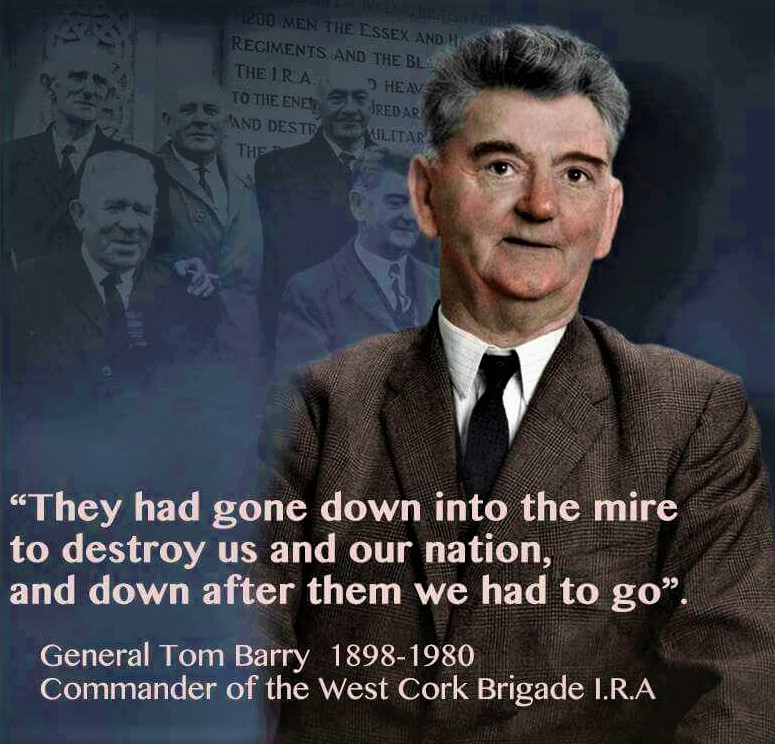

For as Barry had later declared, “they had gone in the mire to destroy us and our nation and down after them we had to go”.

When the fighting was finally finished many of the Volunteers were visibly in shock, most of whom had never engaged in combat prior to Kilmichael. Barry, ever the soldier and commander, formed the combatants into their ranks and drilled them on the roadside to restore order before once again marching cross country with their wounded and dead.

The ambush at Kilmichael left 17 of the 18 British officers present dead, one of whom escaped the battle only to seek refuge at an IRA safe house. While here he was recognised by two IRA men who were staying in the house as being responsible for the murder of an unarmed local only a few weeks prior and was thus executed with his own weapon. The sole-survivor of the battle was taken for dead, by both the IRA and British reinforcements, and only found to be alive when a doctor later noticed he still had a feint pulse. Speaking of the enemy, a Volunteer who fought at Kilmichael described how they fought courageously up until they were all “accounted for”. Such is the valour of men, such is the brutality of war, such is the price of Empire. Of the IRA casualties, three would be fatal. Vol. Michael McCarthy of Dunmanway and Vol. Jim O’Sullivan of Kilmeen, Clonakilty bought died at the ambush site while Vol. Pat Deasy, aged just 16 years, of Kilmacsimon, Bandon surcumbed to his wounds a few hours later.

The success of the Kilmichael Ambush shook the British establishment, both in Ireland and London, to it’s very core. Not only did it do untold damage to the morale of the occupying forces, it also instilled a much needed morale boost in the IRA units engaging the enemy throughout Ireland. It reinforced the importance of the Flying Column organisational method, and proved to many that the IRA had the capability of truly bringing the fight to the British invaders. This rag-tag ensemble of farm labourers, builders and students with little to no combat experience managed to annihilate a battle-hardened and ruthless enemy. The Auxiliaries, along with the regular RIC divisions including the Black ‘n’ Tans and the regular British Army troops, had a fierce reputation around the country for their brutal treatment of not only captured insurgents, but also of the wider general population.

These men were in effect hired mercenaries that were trained and blooded during the First World War, and with no work in post-war England were recruited to come to Ireland to quell the growing tide of anti-colonial resistance that was beginning to sweep the country. And sure enough, they did their upmost to break the spirit of the people and to make it ever so unappealing to be supportive of, or even sympathetic to, the forces of the Irish Republic. But alas, they failed. They failed because people like Tom Barry and those that fought with him at Kilmichael took it upon themselves to strike a blow for the freedom of the ancient Irish nation. They failed because the people of Ireland, despite the social conditioning of centuries of colonial rule, yearned for the chance to take control of their own destinies. They failed because every empire that crosses foreign shores to unjustly and mercilessly conquer another people will inevitably fall when met with the unified voice of a risen people.

But where the Auxies failed in 1920, many more still seek to prevail today. They seek to portray the struggle for full Irish independence as a finished fight. They seek to promote historical revisionism and sell it as a token of a “renewed relationship”. They seek to instil the idea of two separate people, of two separate nations, and they seek to utilise the forces of regression to counter any growing dissention among the masses. In every generation of the fight for national liberation those who took up arms against the oppressors did so not out of hatred or contempt for their fellow human being, but out of love and the universal desire for liberty. From Kilmichael to Warrenpoint, from Vinegar Hill to the Curlews Pass, though the participants change, the motive remains the same; for Irish liberation and against British imperialism. And for the liberty of the masses against their exploitation by those in power.

We in the Republican Socialist Movement, whose foundations were laid in the blood of our martyrs, remain today committed to the very cause of those who fought at Kilmichael – for a united Irish Republic. But, more crucially, a Socialist Republic. Our understanding of politics states that imperialism is but the highest stage of capitalism, by which we mean the systematic exploitation of “weaker” nations by those with the means to do so. Therefore, we find it only natural that our opposition to imperialism and our opposition to capitalism are but two sides of the same coin. By this logic we are against exploitation in whatever form it exists, whether against the worker or entire peoples and nations. And we view those who either prosper from either, or work to the benefit of either, in the same light; as counter-revolutionaries and enemies of the working-class.

No doubt throughout Ireland you will find many of these counter-revolutionaries attempting to claim this very cause which we commemorate today. Usurpers and pretenders who have given nothing to the cause of the Republic, and in many cases, acted against it. Firstly, the gombeen politicians who have exploited our revolutionary past for their own personal gains and who take an active part in the subjugation of our people in the Occupied Six Counties.

But Barry himself said “…there will be no real peace in Ireland until the crime of partition in Ireland is ended, and until Ireland is again a united nation under one government of the Republic”.

The cause for which Tom Barry and his comardes fought for at Kilmichael, and in the years after, was one of Irish unification under the Republic proclaimed in 1916, yet many who claim the mantle of Republicanism shirk from the very mention of Irish Unity. Those who ignore the cause of the Republic have no right to claim it’s legacy, and this applies equally to the rising forces of the political right in Ireland.

These new Irish “patriots”, whose ranks are swolen with middle-aged men who didn’t lift a finger against foreign invasion when our comrades were being gunned down in the streets and their own homes. These draft-dodgers and shite-talkers who desecrate our Republican flag with their neo-fascist ideologies. Who model themselves on the likes of the anti-Irish EDL and share platforms with sectarian hate-mongers. These are but a flash in the pan, without the hearts or the heads to sustain any force of strength on the steets. Their threat is real, but one which is destined to fail. Just like the apparent ascension of the Blueshirts as a militant street movement was physically quelled by the likes of Tom Barry, so too will these modern pretenders. On the 13th of August 1933 Barry travelled to Dublin with members of the Cork IRA to oppose and confront a Blueshirt march, but O’Duffy cowared at the prospect of coming to blows with militant republicanism. The Republicans marched anyway, and took the batton blows of the State forces for their effort. Scenes which were echoed outside of Leinster House on the 11th of October this year. History is cyclical, and we in the Republican Socialist Movement will continue to stand with our comrades in the broad Republican Left against the rise of this fascist scourge. And like Barry, we will do so with full determination and conviction in our cause; the cause of the Irish Republic, the cause of the “men of no property”, the cause of the working-class.

“…oh! Barry’s gone let Munster weep, his pleading ghost cries in the night,

But the Munster rose will only bloom again when Munster men join freedom’s fight.”